An Unnecessarily Long-Winded Introduction to the Essence of Datalog¶

In this post, I’ll gradually build up to a naive implementation of the Datalog engine. An updated version of this post can be found here

Datalog Concepts¶

Let’s start with a simple Datalog Program.

We can have simple facts in our database. e.g. Bob is a man. Abe is a man. In Datalog, we write it as:

man("Bob")

man("Abe")

man is like a table in a database. man("Bob") is a relation in that table. We’ll also call it a base relation.

Next, we create the business logic i.e. rules.

Someone is a person if he is a man

person(X) :- man(X)

person(X) is a derived relation, as it is derived from some base relation man(X). This is similar to a view in the database.

X is a logical variable. So man(X) could be used to refer to all man relations in the database.

from typing import *

from dataclasses import dataclass

from pprint import pprint

We can create a logical variable like this:

@dataclass(frozen=True)

class Variable:

name: str

X = Variable('X')

A relation could be:

man("Bob")

parent("John", "Chester") # John is a parent of Chester

It could also be components of a rule e.g.

man(X) or person(X) in person(X) :- man(X)

So a relation has a name(e.g. parent) and a list of attributes(e.g. "John" and "Chester" or X).

@dataclass(frozen=True, eq=True)

class Relation:

"""

man("Bob) is Relation("man", ("Bob",)) # ("Bob",) is a single valued tuple

parent("John", "Chester") is Relation("parent", ("John", "Chester"))

man(X) is Relation("man", (Variable("X"),))

"""

name: str

attributes: Tuple

A rule could be:

person(X) :- man(X)i.e.Xis a person if he is man.father(X, Y) :- man(X), parent(X, Y)i.e.Xis a father ofYifXis a man andXis the parent ofY

A rule has:

a head relation which is on the left of the

:-symbol e.g.person(X)andfather(X, Y)abovea body of relations which is on the right of the

:-symbol e.g.man(X)andman(X), parent(X, Y)above

Since Datalog is declarative, the order of the relations in the body does not matter. Both the statements below have the same meaning:

father(X, Y) :- man(X), parent(X, Y)

father(X, Y) :- parent(X, Y), man(X) # reversing the order does not matter

So, the body can be represented as a set

@dataclass(frozen=True, eq=True)

class Rule:

head: Relation

body: Set[Relation]

The last element of Datalog is the query. The simplest query is no rules, just facts.

Given:

man("Abe)

man("Bob")

woman("Abby")

A query could be: man(X) # Find me all men

The query should return: {man("Bob"), man("George")}

This would be similar to a SQL query select * from man

Simple Relation Query¶

The simplest query is to find a matching relation. Taking the above example, let’s code that up in Python.

X = Variable('X')

abe = Relation("man", ("Abe",))

bob = Relation("man", ("Bob",))

abby = Relation("woman", ("Abby",))

database = {abe, bob, abby}

no_rules = []

query = Relation("man", (X,))

For some function run_simplest, I expect:

assert run_simplest(database, no_rules, query) == {abe, bob}

The simplest run would iterate through all the facts and filter those facts that match the query by relation name.

def name_match(fact: Relation, query: Relation) -> bool:

return fact.name == query.name

def filter_facts(database: Set[Relation], query: Relation, match: Callable) -> Set[Relation]:

return {fact for fact in database if match(fact, query)}

def run_simplest(database: Set[Relation], rules: List[Rule], query: Relation) -> Set[Relation]:

return filter_facts(database, query, name_match)

assert run_simplest(database, no_rules, query) == {abe, bob}

Let’s add some facts of length two:

parent("Abe", "Bob") # Abe is a parent of Bob

parent("Abby", "Bob")

parent("Bob", "Carl")

parent("Bob", "Connor")

parent("Beatrice", "Carl")

I may want to query who are the parents of Carl

parent(X, "Carl") should return {parent("Bob", "Carl"), parent("Beatrice", "Carl")}

parent(X, "Carl") is similar to select * from parent where child = "Carl" if there was a table parent with columns parent and child)

The beauty of Datalog is that you can ask the inverse without additional code e.g. Who are the children of Bob

parent("Bob", X) should return {parent("Bob", "Carl"), parent("Bob", "Connor")}

Let’s code that up. Also from now on, I’m going to make a helper functions to make it easy to express relations like the lambda parent below.

parent = lambda parent, child: Relation("parent", (parent, child))

database = {

parent("Abe", "Bob"), # Abe is a parent of Bob

parent("Abby", "Bob"),

parent("Bob", "Carl"),

parent("Bob", "Connor"),

parent("Beatrice", "Carl")

}

Now, to the implementation. For a query to match, an argument at position N in the query should match the argument at position N in the fact.

For e.g

assert query_variable_match(parent("A", "Bob"), parent(X, "Bob") ) == True

Logical variables are special. They get a free pass like X above.

def query_variable_match(fact: Relation, query: Relation) -> bool:

if fact.name != query.name:

return False

# TODO: zip is duplicated?

for query_attribute, fact_attribute in zip(query.attributes, fact.attributes):

if not isinstance(query_attribute, Variable) and query_attribute != fact_attribute:

return False

return True

assert query_variable_match(parent("A", "Bob"), parent(X, "Bob") ) == True

assert query_variable_match(parent("A", "Bob"), parent("A", X)) == True

assert query_variable_match(parent("A", "NoMatch"), parent(X, "Bob") ) == False

def run_with_filter(database: Set[Relation], rules: List[Rule], query: Relation) -> Set[Relation]:

return filter_facts(database, query, query_variable_match)

So does it work?

parents_carl = run_with_filter(database, [], parent(X, "Carl"))

assert parents_carl == {parent("Bob", "Carl"), parent("Beatrice", "Carl")}

children_bob = run_with_filter(database, [], parent("Bob", X))

assert children_bob == {parent("Bob", "Carl"), parent("Bob", "Connor")}

Simple Rule Query¶

Let’s add a rule to our program.

human(X) :- man(X) # You are human if you are man.

An example database below:

man("Bob")

man("George")

animal("Tiger")

Query:

human(X) # Find me all humans

The query should return:

{human("Bob"), human("George")}

man = lambda x: Relation("man", (x,))

animal = lambda x: Relation("animal", (x,))

human = lambda x: Relation("human", (x,))

X = Variable("X")

head = human(X)

body = [man(X)]

human_rule = Rule(head, body) # No pun was intended

database = {

man("Abe"),

man("Bob"),

animal("Tiger")

}

rules = [human_rule]

query = human(X)

For each rule, for each relation in it’s body, if it matches with any of the facts in the database,

then get the attributes of that fact and create a derived relation with those attributes.

E.g., since we have man("Abe") and our rule human(X) :- man(X), we add a derived relation to our database human("Abe")

def match_relation_and_fact(relation: Relation, fact: Relation) -> Optional[Dict]:

if relation.name == fact.name:

return dict(zip(relation.attributes, fact.attributes))

def match_relation_and_database(database: Set[Relation], relation: Relation) -> List[Dict]:

inferred_attributes = []

for fact in database:

attributes = match_relation_and_fact(relation, fact)

if attributes:

inferred_attributes.append(attributes)

return inferred_attributes

def evaluate_rule_simple(rule: Rule, database: Set[Relation]) -> Set[Relation]:

relation = list(rule.body)[0] # For now, our body has only one relation

all_matches = match_relation_and_database(database, relation)

# We use the Python feature below that if we call `values` on a dictionary,

# it will preserve the order that was given when the dictionary was created

# i.e. in the `zip` inside `match_relation_and_database`. Thank God.

return {Relation(rule.head.name, tuple(attributes.values())) for attributes in all_matches}

This evaluate_rule_simple can be passed to a function which will evaluate it on each rule for the database to generate the final knowledge base.

def generate_knowledgebase(evaluate: Callable, database: Set[Relation], rules: List[Rule]):

knowledge_base = database

for rule in rules:

evaluation = evaluate(rule, database)

knowledge_base = knowledge_base.union(evaluation)

return knowledge_base

And finally, we have

def run_rule_simple(database: Set[Relation], rules: List[Rule], query: Relation):

knowledge_base = generate_knowledgebase(evaluate_rule_simple, database, rules)

return filter_facts(knowledge_base, query, query_variable_match)

# Test Cases

simplest_rule_result = run_rule_simple(database, rules, query)

assert simplest_rule_result == {human("Abe"), human("Bob")}, f"result was {simplest_rule_result}"

Logical AND Query¶

Next, we introduce logical AND(conjunction). i.e. Given

parent("Abe", "Bob"), # Abe is a parent of Bob

parent("Abby", "Bob"),

parent("Bob", "Carl"),

parent("Bob", "Connor"),

parent("Beatrice", "Carl"),

man("Abe"),

man("Bob"),

woman("Abby"),

woman("Beatrice")

We’d like to find all the fathers in the house. A person is a father if he is a parent and he is a man. i.e.

father(X, Y) :- parent(X, Y), man(X)

X = Variable("X")

Y = Variable("Y")

woman = lambda x: Relation("woman", (x,))

father = lambda x, y: Relation("father", (x, y))

database = {

parent("Abe", "Bob"), # Abe is a parent of Bob

parent("Abby", "Bob"),

parent("Bob", "Carl"),

parent("Bob", "Connor"),

parent("Beatrice", "Carl"),

man("Abe"),

man("Bob"),

woman("Abby"),

woman("Beatrice")

}

father_rule = Rule(father(X, Y), {parent(X, Y), man(X)})

rules = [father_rule]

query = father(X, Y)

How does the match change? We need to add logic for the conjunction i.e. when we match the body to the facts, we have to check if the attributes of the facts match across the entire body,

e.g. for the body parent(X, Y), man(X)

parent(“Abe”, “Bob”), man(“Abe”) is a match as there is a common value

Abeacross the entire body at same place asX.parent(“Abby”, “Bob”) does not match as there is no

man("Abby").

Let’s first code up this common value logic as has_common_value. We also have to start pairing variables to values e.g. {'X': 'Abe'}

This combination below:

has_common_value({ X: 'Abe', Y: 'Bob'}, {X: 'Abe'}) should return True

def has_common_value(attrs1: Dict[Variable, Any], attrs2: Dict[Variable, Any]) -> bool:

common_vars = set(attrs1.keys()).intersection(set(attrs2.keys()))

return all([attrs1[c] == attrs2[c] for c in common_vars])

Once we have that, we know that match_relation_and_database will return as before, a list of body attributes which each match a fact in the database. It’s time to conjunct. We may get some input like:

[[{X: 'Bob', Y: 'Carl'}, # <= All facts that match parent(X,Y)

{X: 'Beatrice', Y: 'Carl'},

{X: 'Abe', Y: 'Bob'},

{X: 'Abby', Y: 'Bob'},

{X: 'Bob', Y: 'Connor'}],

[{X: 'Bob'}, # <= All facts that match man(X)

{X: 'Abe'}]]

For the body man(X), parent(X, Y), we expect back from a function conjunct:

[{X: 'Bob', Y: 'Carl'},

{X: 'Abe', Y: 'Bob'},

{X: 'Bob', Y: 'Connor'}]

Just hacking it for now.

def conjunct(body_attributes: List[List[Dict]]) -> List:

# TODO: Does not cover body lengths greater than 2

result = []

if len(body_attributes) == 1:

return body_attributes[0]

attr1 = body_attributes[0]

attr2 = body_attributes[1]

for a1 in attr1:

for a2 in attr2:

_c = has_common_value(a1, a2)

if _c:

result.append({**a1, **a2})

return result

I also realized that though the body can return many attributes which have ‘conjuncted’, we only need those which are in the head.

e.g. for a rule relation1(X) :- relation2(X,Y), relation3(X), relation1 just needs X so I’ll just pull that.

def rule_attributes(relation: Relation, attr: Dict[Variable, Any]) -> Tuple:

return tuple([attr[a] for a in relation.attributes])

So the final evaluate function becomes

def evaluate_logical_operators_in_rule(rule: Rule, database: List[Relation]) -> Set[Relation]:

body_attributes = []

for relation in rule.body:

_attributes = match_relation_and_database(database, relation)

body_attributes.append(_attributes)

attributes = conjunct(body_attributes)

return {Relation(rule.head.name, rule_attributes(rule.head, attr)) for attr in attributes}

def run_logical_operators(database: Set[Relation], rules: List[Rule], query: Relation):

knowledge_base = generate_knowledgebase(evaluate_logical_operators_in_rule, database, rules)

return filter_facts(knowledge_base, query, query_variable_match)

Let’s test that it works for single relation bodies, preventing any regressions.

simple_conjunct_rules = [Rule(human(X), {man(X)})]

assert run_logical_operators(database, simple_conjunct_rules, human(X)) == {human("Abe"), human("Bob")}

And our final test

assert run_logical_operators(database, rules, query) == {father("Abe", "Bob"), father("Bob", "Carl"), father("Bob", "Connor")}

Logical OR Query¶

Logical OR is just specifying two separate rules with the same head. E.g.

human(X) :- man(X)

human(X) :- woman(X)

In Python, given:

database = {

animal("Tiger"),

man("Abe"),

man("Bob"),

woman("Abby"),

woman("Beatrice")

}

man_rule = Rule(human(X), {man(X)})

woman_rule = Rule(human(X), {woman(X)})

rules = [man_rule, woman_rule]

query = human(X)

assert run_logical_operators(database, rules, query) == {

human("Abe"),

human("Bob"),

human("Abby"),

human("Beatrice")

}

Recursive Relations Query¶

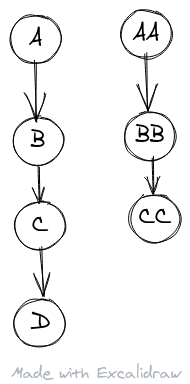

Next, we introduce the reason why we are interested in Datalog. Datalog intuitively captures hierarchies or recursion. E.g. we want to find all who are ancestors of someone. Given:

parent("A", "B") # A is the parent of B

parent("B", "C")

parent("C", "D")

parent("AA", "BB")

parent("BB", "CC")

A parent X of Y is by definition an ancestor.

ancestor(X, Y) :- parent(X, Y)

If you are a parent of Y and Y is an an ancestor, then you are an ancestor as well.

ancestor(X, Z) :- parent(X, Y), ancestor(Y, Z)

Query: ancestor(X, Y) should return all the parents above as ancestors

ancestor("A", "B") # A is the ancestor of B

ancestor("A", "C") # A -> B -> C

ancestor("A", "D") # A -> B -> C -> D

ancestor("B", "C")

ancestor("B", "D") # B -> C -> D

ancestor("C", "D")

ancestor("AA", "BB")

ancestor("AA", "CC") # AA -> BB -> CC

ancestor("BB", "CC")

In Python,

ancestor = lambda ancestor, descendant: Relation('ancestor', (ancestor, descendant))

database = {

parent("A", "B"),

parent("B", "C"),

parent("C", "D"),

parent("AA", "BB"),

parent("BB", "CC")

}

X = Variable("X")

Y = Variable("Y")

Z = Variable("Z")

# ancestor(X, Y) :- parent(X, Y)

ancestor_rule_base = Rule(ancestor(X, Y), [parent(X, Y)])

# ancestor(X, Z) :- parent(X, Y), ancestor(Y, Z)

ancestor_rule_recursive = Rule(ancestor(X, Z), {parent(X, Y), ancestor(Y, Z)})

rules = [ancestor_rule_base, ancestor_rule_recursive]

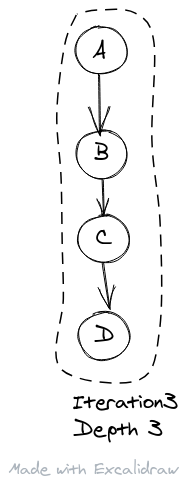

Alright, let’s dive into this. What is different from run_logical_operator? It’s the hierarchy or recursion. If you see it as hierarchy(I’m visualizing this as a tree), one has to keep on going until we reach the top of the tree.

So let’s imagine how we would process the above example. In the first pass, we would do the simplest inference from base fact to derived fact using the base rule of ancestor(X, Y) :- parent(X, Y).

Showing one hierarchy as an example(starting from A).

Pass 1: Base Facts and Inferred facts i.e. KnowledgeBase1

parent("A", "B"),

parent("B", "C"),

parent("C", "D"),

parent("AA", "BB"),

parent("BB", "CC")]

# ----------------- New inferred facts below --------------

ancestor("A", "B"),

ancestor("B", "C"),

ancestor("C", "D"),

ancestor("AA", "BB"),

ancestor("BB", "CC")

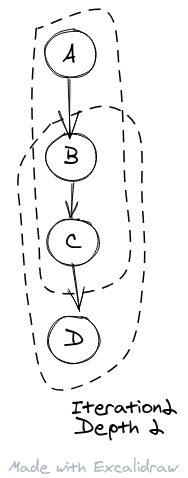

Now that’s done, we can focus on inference from a combination of inferred facts and base facts to new inferred facts using the recursive rule ancestor(X, Z) :- parent(X, Y), ancestor(Y, Z). For e.g. in KnowledgeBase1, we have parent("C","D") and ancestor("B", "C") , so we can infer the fact ancestor("B", "D") i.e grandparents. We keep on doing this till we get:

Pass 2: KnowledgeBase2

parent("A", "B"),

parent("B", "C"),

parent("C", "D"),

parent("AA", "BB"),

parent("BB", "CC")

ancestor("A", "B"),

ancestor("B", "C"),

ancestor("C", "D"),

ancestor("AA", "BB"),

ancestor("BB", "CC")

# ----------------- New inferred facts below --------------

ancestor("A", "C")

ancestor("B", "D")

ancestor("AA", "CC")

Do we stop? No, we have to keep on going till we find all the ancestors. Let’s apply the rules to KnowledgeBase2 and get

Pass 3: KnowledgeBase3

parent("A", "B"),

parent("B", "C"),

parent("C", "D"),

parent("AA", "BB"),

parent("BB", "CC")

ancestor("A", "B"),

ancestor("B", "C"),

ancestor("C", "D"),

ancestor("AA", "BB"),

ancestor("BB", "CC")

ancestor("A", "C")

ancestor("B", "D")

ancestor("AA", "CC")

# ----------------- New inferred facts below --------------

ancestor("A", "D")

i.e A is the great grand parent of D

Do we stop? Yes(if you look at the above example), but the computer does not know that. There could be new inferred facts, so let’s try again for KnowledgeBase4.

Pass 4: KnowledgeBase4

parent("A", "B"),

parent("B", "C"),

parent("C", "D"),

parent("AA", "BB"),

parent("BB", "CC"),

ancestor("A", "B"),

ancestor("B", "C"),

ancestor("C", "D"),

ancestor("AA", "BB"),

ancestor("BB", "CC")

ancestor("A", "C")

ancestor("B", "D")

ancestor("AA", "CC")

ancestor("A", "D")

# ----------------- New inferred facts below --------------

No New Facts

Aha! There are no more new inferred facts. If we do another pass on KnowledgeBase4, it would come out the same. So we can stop!

So the logic to stop would be:

Take the output of each iteration. If it matches the input to that iteration, stop(as we did not learn any new inferred facts). If not a match, then run another iteration. Let’s call this method iterate_until_no_change.

def iterate_until_no_change(transform: Callable, initial_value: Set) -> Set:

a_input = initial_value

while True:

a_output = transform(a_input)

if a_output == a_input:

return a_output

a_input = a_output

Now, we already have evaluate_logical_operators_in_rule. That will be our transform function above. So putting this all together below.

def run_recursive(database: Set[Relation], rules: List[Rule], query: Relation):

transformer = lambda a_knowledgebase: generate_knowledgebase(evaluate_logical_operators_in_rule, a_knowledgebase, rules)

knowledgebase = iterate_until_no_change(transformer, database)

return filter_facts(knowledgebase, query, query_variable_match)

Let’s define the query

query = ancestor(X, Y)

recursive_result = run_recursive(database, rules, query)

expected_result = {

ancestor("A", "B"),

ancestor("B", "C"),

ancestor("C", "D"),

ancestor("AA", "BB"),

ancestor("BB", "CC"),

ancestor("A", "C"),

ancestor("B", "D"),

ancestor("AA", "CC"),

ancestor("A", "D")

}

assert recursive_result == expected_result, f"{recursive_result} not equal to {expected_result}"

Let’s explore other queries we can ask.

Is AA the ancestor of C?(No! Such an impolite question)

query = ancestor("AA", "C")

assert run_recursive(database, rules, query) == set()

What if I want to find all ancestors of C?

query = ancestor(X, "C")

assert run_recursive(database, rules, query) == {ancestor("A", "C"), ancestor("B", "C")}

What if I want to find who all are the descendants of AA. Again, use the same query but just reverse the order!

query = ancestor("AA", X)

assert run_recursive(database, rules, query) == {ancestor("AA", "BB"), ancestor("AA", "CC")}

Finally, who are the intermediates between A and D i.e. B and C.

Z is an intermediate of X and Y if X is it’s ancestor and Y is its descendant.

intermediate(Z, X, Y) :- ancestor(X, Z), ancestor(Z, Y)

In Python,

intermediate = lambda intermediate, start, end: Relation("intermediate", (intermediate, start, end))

intermediate_head = intermediate(Z, X, Y)

intermediate_body = {ancestor(X, Z), ancestor(Z, Y)}

intermediate_rule = Rule(intermediate_head, intermediate_body)

rules = [ancestor_rule_base, ancestor_rule_recursive, intermediate_rule]

query = intermediate(Z, "A", "D")

assert run_recursive(database, rules, query) == {intermediate("B", "A", "D"), intermediate("C", "A", "D")}

That’s it! If you found it interesting, check out Mercylog, a Datalog inspired library in Python.

Extra Extra. Read All About It¶

This post was inspired by this post.

SQL does support recursion. I just find Datalog has a cleaner syntax.

One aspect of Datalog being declarative is that the order of rules does not matter either. So technically, instead of

rules = [rule1, rule2], we could have usedrules = frozenset([rule1, rule2]). The latter is a bit more clutter so I used simple lists.